Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels by Hsu-Ming Teo (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012)

After writing the review of Sarah Morgan’s excellent category romance novel, Lost to the Desert Warrior, I began to be slightly fascinated with the idea that, in a post 9/11 world, there exists an entire sub-genre of romance featuring Middle Eastern heroes (and sometimes heroines). How does this fit with our culture as Westerners, with the current political and economic climate, and with the larger genre of romance?

When you’re a librarian, your life is more than “ask a question, find an answer.” Rather, it’s closer to “ask a question, ask a bunch more questions, read a crap ton of interesting sources, and immerse yourself in a subject” but it’s a process I clearly enjoy otherwise I wouldn’t do it as often as I do. A large part of my happiness in learning about this topic came from the discovery of the book that has given me a framework and staring point for exploration, namely cultural historian Hsu-Ming Teo‘s outstanding academic work, Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012).

Incredibly well-written and exhaustively researched, Teo’s prose is riveting; this Australian author of both nonfiction and fiction makes the historical context of the sheikh in romance novels come alive. Because the subject is fascinating and lends itself to an understanding of current romance literature (both the writer and the reader can benefit greatly from the book), I’ve chosen to indulge myself in making this a multi-part blog post. This first installment will focus on the complex history of “the Orient” and the relationship of Western Europeans to this region.

First Things First. What Is a Sheikh?

A historical photo of a Bedouin family, circa the turn of the 20th century.

Let’s start first by defining some key terms, for example, what is a sheikh? Yes, that word can be spelled two ways “sheik” and “sheikh” and they both are correct with the same definition: simply put, a sheik is a title referring to man who is the head of a family. Done. That’s it.

Yet the word becomes more complex. It can be a gesture of respect toward a man who might also be a religious leader, but the term is largely rooted in the Bedouin community, indicating not just the head of a family but possibly of a tribe. The Bedouin people are the desert nomads of North Africa and the Middle East, traditionally focusing on animal husbandry as a way of life. Nowadays, Bedouins, who possess a rich culture of self-sufficiency and familial interdependence, are as likely to drive Land Rovers as ride a camel, particularly with government encroachment and nationalization of their lands. But no one disputes that the title of sheikh refers to a strong male leader in this environment.

The Orient Is Not a Place

The Orient can’t be found on any map…because it doesn’t exist.

So why the word “orientalism”? It’s a term confusing to modern readers since the Orient or the word Oriental has come to mean the many countries and cultures of Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, etc.) but in actuality this word is usually a generational one which has fallen out of favor for a specific reason. That is, there is no such place as the Orient.

Really. Go find your globe or a modern map and look for it. It doesn’t exist. To find something labeled “the Orient” you’d have to dig up an antique map from the 1500s or earlier, back when cartographers read sketchy sailor accounts or interviewed drunken midshipmen at the local tavern in order to produce horrifyingly inaccurate maps which were then used to pitch “Let’s Discover the Riches of the Orient” sailing cruises to aristocratic funders who would likely feel at home one of those ruthless time-share sales environments. Next to “the Orient” was probably the picture of a giant sea-squid or a mermaid and the phrase “Here be monsters.”

For Western Europeans using the term “Orient” in this time period, they were referring to the North African, Middle Eastern and Eastern Europe laying along the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

With this in mind, the Orient was then historically a synonym for the unknown East, and if that meant the Near East (like Turkey or Egypt) or the Far East (like China or Mongolia) Western Europeans didn’t care. It just meant “different from us and damn far away.” For most of the medieval and Renaissance periods, a geographic understanding of what areas are included in this sweeping term (which I refuse to use) can be absorbed by understanding where the Ottoman Empire existed from about the eighth century to 1918. North Africa, the Middle East, and Turkey are the predominant regions which promoted so much fascination and antipathy on the part of Western Europe and later the Americas. These areas were and continue to be dominated by Islam as a unifying religion and the shared background of Arabic culture.

After it’s publication in 1978, Edward Said’s book Orientalism quickly became the seminal work used to understand the complex and troubled relationship between the West and the Middle East.

Orientalism is a whole different animal. While in the past this term was used to refer to Western art or literature which attempted to use the culture of the Middle East or North Africa as a theme, the modern definition is the one promoted by scholar Edward Said in his 1978 groundbreaking work, Orientalism. Said put forth the idea that orientalism was any academic, artistic or popular work which “imagines, emphasizes, exaggerates and distorts differences of Arab peoples and cultures as compared to that of Europe and the U.S. It often involves seeing Arab culture as exotic, backward, uncivilized, and at times dangerous.”

For a variety of reasons (which I will explore in the posts on this topic) Western culture has become bizarrely focused on the “sexual fecundity and sensual appeal” of this area of the world. (Teo, p. 5) This is likely the historic juxtaposition between a culture which embraces love and sex in both a religious and cultural context, and the Western European tradition of Christian suppression and oppression of anything sexual in nature. Seeing how this juxtaposition has been handled throughout history actually gives us a tremendous opportunity to interpret modern sheikh romances with a new eye.

Modern sheikh novels often have compelling heroes and focus on emotional commonalities while still using the common trope of a character (usually the heroine) being immersed in a culture that is foreign, and one often laden with sensuality.

As Teo says in her book, “These novels certainly rehash classic Orientalist discourses, but not necessarily with the aim of differentiating, distancing and denigrating the Arab or Muslim in modern Western society. Because of the formal plot demands of the genre of romantic fiction…, cultural commonality and shared human interests and emotions are often emphasized instead of ineluctable difference.” (p. 10) In other words, while these books still oversimplify or gloss over the cultural meaning behind the “sheikh” title or have a hero who initially fits the stereotype of perhaps a powerful man unenlightened by modern gender politics (and this is not universal in these books), the same novels often celebrate the stability and strength of Arab families, contrasting this ideal against high Western divorce rates. This places modern sheikh novels in a strange limbo, one in which there are still orientalist themes present, but often where the novel itself promotes a view of Arab culture which actively fights the stereotypes prevalent in modern Western culture. (More on this in a later post!)

The Crusades: Bringing People Together Since the Eleventh Century

Even prior to the Crusades, trade with the Middle East was associated with items that delighted the senses – spices and aromatic oils. More fascinatingly is the fact that just like the majority of Western philosophy, history and medicine – which owes its preservation to the erudite Arab scholars which preserved all the Greek and Roman works that monasteries burned or didn’t preserve during it’s Dark Ages – the West owes its view of love to Arab culture.

The Muslim world had an established culture of romantic love long before the Europeans birthed courtly troubadours singing about knights satisfied by longing glances and a scarf around the arm prior to being killed while jousting. This ideal of unrequited, unconsummated love, which we associate with high medieval Western culture, is actually stolen kit and caboodle right from Arabic and Persian bards who felt this feeling was the ideal to aim for, a kind of martyr’s death, calling it “Udhrah love.” (Teo, p. 29)

Moorish architecture and art still abound throughout Spain and Portugal, dating back to this period where spreading the concept of Urdrah love through music and literature swept through European courts.

When the Muslim invaders decided the Spanish peninsula looked as good as where they currently stood in Morocco, the people who would become known as the Moors invaded that region, spreading art, music, advanced medicine – and thankfully the practice of bathing – to a group of Europeans living in comparatively barbaric conditions. This allowed translated Arabic poetry and literature to make the rounds of nearby European courts, stopping first in the French region of Provencal, where Udhrah love gained a toehold in the bardic traditions of those areas. Because of the scholarly understanding of where these stories originated, the Middle East and North Africa were seen as possessing “a sophisticated system of beliefs about love, seduction, sensuality, and the pleasure of the senses.” (Teo, pp. 30-31) Because of this association and various political factors, Islamic literature and poetry would spur Western literature’s attempt to interpret the relationship between the Near East and the West through the vehicle of romance.

The Crusade Romance: Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Pope Urban II giving the call to arms to warriors willing to take up the cross and take back the major historic sites of Christianity. Illumination from the Livre des Passages d’Outre-mer, of c 1490 (Bibliothèque nationale de France) via Wikipedia.

The first examples of sheikh-style romance actually were written at the time of the early Crusades in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Crusades were initially spurred by the exhortation of Pope Urban II in 1095 for knights “to take up the cross” (which the French translated as crusade) in order to reclaim the holy sites of Christianity for the Catholic Church and Western Europeans. Clearly not caring that there were holy sites for two other major religions in the region, Urban II also didn’t seem to be too perturbed that he had stirred up what would become a few centuries of warfare, with the much vaunted sacred locations vacillating back and forth between the Christians and the Ottoman Empire.

Yet more than one modern scholar has drawn strong connections between the code of honor held by European knights in the High Middle Ages and the Saracen or Turk of this same time period. Rules of combat, styles of warfare and the treatment of high-born prisoners aligned between these two groups separated by ethnicity and religion. These similarities, when contrasted so strongly by the startling differences of physical appearance and opposing religions, provided a great deal of fascination for Europeans, an obsession which emerged in Orientalist literature of the time period.

In the literature which used the Crusades as inspiration, “the ultimate triumph was not the death of the Saracen, but his or her conversion to Christianity through love and marriage.” (Teo, p. 31) The common trope was the one seen by modern sheikh romance readers today, namely that of a European, Christian woman kidnapped against her will due to her proximity to the conflict or involvement of her male relatives in the crusades who falls in love with her Arab Muslim captor. While some stories certainly espoused the ideals of romantic love (albeit with a Christian conversion by the hero as a key part of the happily ever after), other stories held horrible warnings for couples without this cleansing sacrament. A child of an Arab/European union is seen as being monstrously deformed until the holy water of baptism morphs him into a normal child; the hero’s dark skin similarly fades to white while undergoing that same religious introduction. (pp. 32-33) Early writers did not shy from laying the emphasis on religion thickly, just so there was no mistake regarding romance inspired by a religious war. Subtlety did not appear to be a High Medieval period trait.

“Count of Tripoli accepting the Surrender of the city of Tyre in 1124,” (1840) by Alexandre-Francois Caminade (Bridgeman Art Library / Chateau de Versailles, France / Giraudon)

The flip side of the gender coin was also visible in literature of this time. While the modern theme of “white Christian sold into slavery” held the test of time into the 20th century, crusade romance even had handsome knights, captured in battle, who fell for clever and beautiful Saracen princesses. These feisty ladies were willing to deceive their powerful fathers, free their lovers, only to run off and get baptized and then married. Hsu-ming Teo offers the excellent observation that while these women were seen by male readers of the time as lustful and unscrupulous (no man of the Middle Ages would encourage a daughter to defy a father), in actuality these women closely resemble our strong modern heroines and provide a contrast to the dishwater European women trapped as subservient pawns to men during this time. (p. 33) Despite cultural and religious differences the high Medieval period loved challenges to romance and was willing to use its heroes and heroines to illustrate how love (and Christianity) would always triumph in a successful marriage.

From Renaissance to Not Quite Enlightenment: A Turning Point Regarding Race

Perhaps the greatest twist for me in reading about the history of the sheikh romance has been the changing concept of what constitutes race, and therefore what a couple is capable of surmounting. Initial European conceptions of race were that a certain skin color denoted an unacceptable religion; with this concept, baptism would render the individual romantically and socially acceptable as a means of repudiating their heritage and proof of embracing European and Christian ideals. (Teo, pp. 34-35) Once race was seen as an unalterable difference which was in itself insurmountable, the interracial love narrative also changed. (Since race is a social construct and not a scientific fact, I encourage anyone interested in exploring the concept from either a historical or biological perspective to take a look at the amazing website, Understanding Race.)

“Othello and Desdemona in Venice” by Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856) via Wikipedia

In Giraldi Cinthio’s short story “Un Capitano Moro” (published in Hecatommithi in 1565), we see the foundation for Shakespeare’s Othello, which was written roughly forty years later in the early 1600s. A Christianized Moor goes from being a hero who saved Venice to the monster who murdered his European wife, Disdemona (Cinthio’s spelling), a wife who, while fighting with her husband prior to her death, warns women not to wed men so totally different from themselves.

This story (seen in translation at the above link) is virtually the exact outline for Shakespeare’s play, with an evil Ensign inciting his normally even-keeled Captain to insane jealousy, planting the seed of his virtuous wife’s infidelity, and driving the man to murder. (Teo, p. 36) Upon realizing how much he loved his wife, the Moor sinks into melancholy and despair and grows to hate the evil Ensign. Arrested and tortured for information by the government of Venice, the Moor withstands the privations of his imprisonment and is finally released, after which time he is anti-climatically murdered by his wife’s kinsfolk in revenge.

“Desdemona Cursed by her Father (Desdemona maudite par son père)” – Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) (Brooklyn Museum) via Wikipedia

Aside from my astonishment at Shakespeare’s flagrant plagiarism (there was no such thing as copyright back then, but the librarian in me is horrified), this story represents a turning point in the romantic European view of race which went from being something linked to religion and therefore possible to “overcome” in the eyes of Europeans, to a deep-seated indicator of true nature. This paradigm shift rendered interracial love by and large an obstacle almost impossible to overcome.

There is also a simplicity in solidifying the view of the “other” by associating skin color with an insurmountable social barrier, a view which has served Western society throughout its history of oppression. In the United States almost a century after Cinthio’s work, the burgeoning American colonies, desperate for labor, had the problem of the discontented freeman without land of their own. Previously having worked for wealthy landowners, both indentured servants from Europe who had pledged their labor for a ticket to the New World and the Africans captured and sold for labor worked side by side in the fields. Both harbored a reasonable hope that they would one day be free of their obligations and certainly held the belief that their children would be free. At the time their contract ended, each worker regardless of race was given their “freedom dues” – usually a gun and a piece of land.

“Bacon’s Rebellion” by Sidney King (1907-2002), National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park

As long as the servant being freed was a Christian, there was no objection from any man being bumped up the social ladder from servant to freeman, a label which still would have been seen as being part of the peasant class. (PBS, Africans in America, “The Terrible Transition”) But by the late seventeenth century, Virginia’s system hit a speed bump when there simply wasn’t enough land for these young men. A group of discontented young men, white and black, rioted in 1676 in what would become known as Bacon’s Rebellion.

The answer to the banner’s question is that this person used to be both a man and a brother to the white men working alongside him in servitude.

The elite of Virginia responded by not only putting down the rebellion, but solving their labor problem by turning all their attention from indentured servitude as the answer to the men and women bringing brought over from Western Africa. Wanting an easy way of not only having a permanent servant class but also a simple way to identify who was in service, these governing men decided skin color was the easiest marker. As historian Edward Morgan puts it, “Slaves could be deprived of the opportunity for association and rebellion. They could be kept unarmed and unorganized. And since color disclosed their probable status, the rest of society could keep close watch on them…” (Edmund S. Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox” The Journal of American History 59, no. 1 (June 1972): 5–29.) For two disparate societies to live cheek by jowl with one another, and for the dominant society to discourage interaction (and particularly to discourage anything resembling sanctioned interracial relationships), a visible difference was crucial. Whether it was the slave collar of ancient Rome or the skin color of the Saracen, this instant visual cue was needed to warn Western Europeans away from the perceived dangers of close association.

Whether it was the writers of the Renaissance and early Enlightenment or the Virginia landowners, this fiction and legislation all points to a key development regarding race. European nations were acquiring colonies which both required cheap labor and often provided non-Christians who appeared visibly different and could fulfill that need. The Ottoman Empire, which had shared a border with Western Europe for centuries, had become enough of an historical threat to warrant the changing view of the Turk or Corsair as having a skin color which provided a window into the person’s true nature, no matter his or her religion. While the adoption of views of race are inherently complex in any society, that this turning point occurred at a time when the Ottoman Empire was being seen as even more of a threat to European nations is hardly coincidental. In actuality the height of the Renaissance and scholarship of the Enlightenment would bring greater polarization between these cultures, with literature and music furthering the promotion of stereotypes and misunderstanding.

Proliferation of Captivity Narratives, and the Fear of “Turning Turk”

The Ottoman Empire was most definitely a threat to Europe, both economically in their stranglehold on the trade to the East using routes through the MIddle East and North Africa traversed for thousands of years, and also in the Ottoman hunger for empire expansion and for slave labor, resulting in them constantly tickling the borders of Western Europe. The trade monopoly was one of the biggest spurs to the courts of Europe to fund discovery expeditions in the hope of finding new routes to the East across seas not dominated by the Ottomans. Signing a peace treaty with Venice in 1573 allowed the empire to consolidate its North African holdings without threat, but a thirteen year war with the Austrian Hapsburgs in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century drained resources on both sides.

Because of this constant tension between political powers, the late Renaissance and Enlightenment periods produced literature with themes involving the Ottomans, with the culture’s beauty and cruelty emphasized according to established Orientalist parameters. With the ongoing conflict with the Austrians and Turkish pirates regularly raiding the Irish and English coasts, captives were regularly taken either for ransom or enslavement.

Scholar Linda Colley in her 2002 work, Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600-1850, estimates that over 20,000 English and Irish men, women and children were sold in the slave markets of Algiers and Istanbul as a result of this accepted practice. Ohio State history professor Robert C. Davis in his 2003 work, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800 (Early Modern History)

, asserts that as many as one million Europeans, taken from the tip of Spain all the way up to Iceland were enslaved by pirates who worked in tandem with the Ottoman Empire during this time period.

The fear this constant threat engendered played out in the over 47 plays written from 1558 to 1642 which held the theme of a European captive at the mercy of a powerful Ottoman overlord. Stories and epic poems produced during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries also possessed this element, often being written from the perspective of the enslaved, a perspective often labeled “the captivity narrative.” Perhaps one of the most well-known fictional accounts of a captivity narrative occurs in Cervantes’ Don Quixote

The fear this constant threat engendered played out in the over 47 plays written from 1558 to 1642 which held the theme of a European captive at the mercy of a powerful Ottoman overlord. Stories and epic poems produced during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries also possessed this element, often being written from the perspective of the enslaved, a perspective often labeled “the captivity narrative.” Perhaps one of the most well-known fictional accounts of a captivity narrative occurs in Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1604, a year after Othello). “The Captive’s Tale” relates the story of a Spaniard who arrives at a tavern with a veiled woman. He proceeds to tell the story of how he was captured and sent to Algeria, where he he fell in love with a wealthy Moorish princess, Zoraida. She returned his love, betrayed her tyrannical father, freed her lover and converted to Christianity in order to marry her man and return to his homeland. Cervantes himself was actually captured by Algerian pirates in 1575 and spent five years in captivity (attempting to escape four times without success) before being ransomed by his family and returning to Madrid. (Irwin Edman in the introduction to Don Quixote) Clearly he had a lot of personal experience to bring to this part of his story. Other narratives, for example, “The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman

” followed the almost identical premise.

The Arabian Nights is the English title for One Thousand and One Nights, with the majority of translations relying heavily on Gallard’s original work.

Probably the most famous story of a slave under a brutal Muslim overload is the Antoine Gallard novel, Les mille et une nuits (Tales from the Thousand and One Nights) published from 1704 to 1717 in multiple volumes which featured translated African and Persian tales. As Gallard was an archeologist – which in this period meant antiquities thief – he possessed some fluency in Arabic, Persian and Turkish. Purportedly possessing a 14th century Syrian manuscript with the tales in it, Ali Baba and Aladdin are thought to be Gallard’s own invention.

Essentially a series of stories within a story, this collection (usually entitled Arabian Nights in English) uses the framework of a Persian king who, having executed his wife for flagrant infidelity comes to the conclusion that women are all the same. Each night this seemingly heartless ruler takes a new concubine to bed and then executes her the following morning to avoid disappointment. When his trusted vizier can no longer find suitable women for the king’s bed, his daughter, Scheherazade volunteers to go. She tells the king a tale but leaves him with the cliffhanger at sunrise, necessitating him calling her back to his bed that night and postponing her execution. This continues for 1,001 nights until the king comes to his senses and realizes that Scheherazade is actually nothing like his dead wife and that he is in love with this clever, loyal woman. Some men are seriously slow on the uptake.

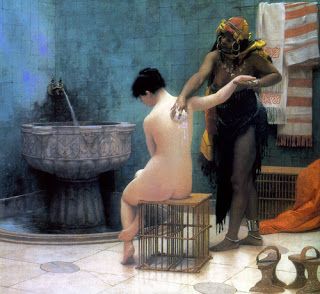

Jean-Léon Gérôme, “The Bath,” ca. 1880-85, Oil on canvas, 29 x 23-1/2 in. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Mildred Anna Williams Collection. An incredibly orientalist painting, the stool she sits on even resembles a cage denoting her captivity.

While captivity narratives attempted to convey the heinous Muslim slave-owners (at a time when Europeans were doing plenty of slave-owning themselves), a main piece of the narrative was the immense pressure placed on captives to convert to Islam, and the captives noble resistance of these efforts. In actuality many captives cheerfully converted to their captor’s religion, the men largely because it enabled them to rise through the ranks and even gain their freedom, while women felt Islam was a religion kinder to women (that’s not a huge compliment given the state of both Catholicism and Protestantism at this time) and offering more rights. (Teo, p. 40) Europeans derogatorily called this conversion process “turning Turk” and the phrase eventually morphed into one insinuating a love of the perceived sexual depravities captives might endure in a harem.

What is fascinating about the captivity narratives from this time period is that rarely are women seen as being in danger of sexual defilement; it is the male captives depicted at risk for rape through sodomy (a danger I would imagine far more of a likelihood in the British navy of the time). Since this theme disappeared in the mid-1700s, right after Britain consolidated its role as a global European power, modern scholars believe the fear of sodomy to indicate the greater cultural anxiety of being “invaded” rather than having any basis the routine rape of male captives, for which there appears to be no evidence. (pp. 42-43)

The harem and what went on behind closed doors became the subject of fascination for Europeans, both in literature and music, yet many works featuring it still managed to insert larger messages about the Western view of the Ottoman Empire and of European views of sexuality.

The Allure of the Harem

The entrance to the harem (women’s quarters) at the Topkapi Sarayi, the famous palace occupied by the head of the Ottoman Empire from 1465 to 1856. The Sultan’s mother, wives, concubines and children, along with the female servants and eunuchs who served them, lived in this wing containing over 100 rooms.

While Western culture saw the harem as a guarded place of sexual license and indulgence populated by sequestered slaves, the reality was anything but. Haram in Arabic means “forbidden” or “sacred” and refers actually to women who choose to wear the veil, keeping their face for their near relatives alone. (Teo, p. 41) While wealthier women were often isolated, most women in Islamic culture of this time enjoyed greater freedom than their Christian counterparts. While calling the women’s quarters a harem was likely to be inaccurate on many levels, the later stranger moniker of seraglio was easier to explain. The Turco-Persian word sarayi (meaning “palace”) was commonly heard by Westerners visiting cities like Istanbul, and confused with the Italian verb serrare meaning “to lock up.” By the end of the 1500s, the French word serail and the English word seraglio did not just refer to a Turkish women’s palace but had become synonymous with “brothel” giving a clear indication of a Western view of such a place. This association became even more popular after Samuel Johnson chose to include it in his dictionary (perhaps for his friend Bothwell who knew far more about brothels than Johnson).

While European men were sure to exclaim “oh, that’s horrible!” in front of the clergy, secretly they dined out on this fantasy of sexual free-for-all (with one man as a focus, ahem) behind harem doors. No matter how inaccurate their perceptions, I think we can safely guess they weren’t fantasizing about converting the ladies within to Christianity.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who not only published her first hand account of Turkey but also brought back the knowledge of smallpox inoculation (the predecessor of vaccination) to England.

Even faced with actual evidence of their misconceptions, artists continued to perpetuate the above perception of the harem and Turkish women. By the mid-18th century, many Western Europeans had visited Turkey, publishing their travel accounts. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), a good friend of Alexander Pope, traveled with her ambassador husband to Turkey, later publishing her first person accounts of what she saw in Turkey. Since actual first person accounts had been written by men (and many of them captives), Montagu’s Turkish Embassy Letters provide a completely different perspective on Turkish culture. Charming, lovely and full of wit, Montagu was received all over the country, and she avidly described the interiors and fashions of the women’s quarters she was invited into. While offering audiences plenty of titillation regarding feasts of the senses, she compared the harems she saw to the 18th century courts she had visited, declaring them in many ways enlightened since women could own property and had a degree of autonomy only dreamed of in the West. (Teo, p. 49) Rather than housing lesbian orgies and naked soaping, Montagu showed Turkish women and children living as loving families, engaging in domestic supervision and embroidery familiar to the middle and upper class women who would read her account. But this actual first-person reality check never quite made it into the male consciousness, at least not in literature, as fiction became more powerful than truth.

Pornography and the Harem Setting

I think what surprises me more than the somewhat pornographic quality of this picture is the lack of pubic hair seen on adult women in this time period.

Lord Byron, that truculent but handsome rake, is often thought by scholars to have successfully laid a titillating foundation for Orientalist pornography as the harem scenes he depicts in The Corsair (1814) and Don Juan

(1819), painting the harem scenes in them with lush sensual images of naked women stretched as far as the male eye could see. (Teo, p. 57) By the 1820s, caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson, a member of the Royal Academy who produced lovely artistic works, was also chased by poverty. He occasionally turned to political caricatures but also made money producing illustrations featuring swarthy, large-penised males presented with pale naked beauties who either preened for his pleasure or caressed him.

Not only is this book still around (and in the public domain, so don’t think you have to pay for it), but it’s been made into a pornographic film numerous times. I know you are shocked by that tidbit, right?

He illustrated one of the most famous pornographic novels, The Lustful Turk, which was never given a named author, but went through multiple revisions and printing throughout the 19th century, beginning in 1828. In this work, the English Emily Barlow is being shipped to a distant relative in India because the man she loves has no fortune (and lacks the gumption to grab her and elope to Gretna Green). On the way, her ship is overtaken by Barbary Pirates and Emily is sold to Ali, the dey of Algiers who rapes her. Recovering from her ordeal she meets other European women in Ali’s harem who have a similar experience, down to the ineffectual European lover who didn’t so much as steal a kiss. Like her predecessors, Emily grows to enjoy sex with Ali, due to his physical endowments, with her fellow Europeans succumbing to his ardor as well.

Scholars argue that The Lustful Turk, like The Sheik which followed it practically a century later, provides the Orientalist opinion that European culture had emasculated its men and distanced its women from their sexuality, both conditions thrown into stark relief when said European women were confronted with hypersexualized Muslim males. The Lustful Turk spawned numerous subsequent novels along the same themes and content (and illustrated), perpetuating the harem motif for European men.

One of the later 20th century sheikh novels (originally published in 1977) sadly involving rape as a plot device. Don’t read it unless you have to do an academic paper on the topic.

Is this all offensive? Hell, yeah, but through these offensive stereotypes of Ottoman men, the real revelation is clearly what the author is saying about the stunted view of sex in Western society. The male view of rape as some terrific trigger to liberate women from the culturally induced frigidity would even be adopted by female novelists (who clearly knew nothing about rape) in the 20th century. This choice gave romance fiction as a whole a taint from which it still hasn’t recovered, with many critics still referring to all romance novels with sexual content as “bodice rippers,” a term which only describes that small subset of romance for which rape is the first sexual encounter between the hero and heroine. (Teo, p. 63)

In my next installment of this series, I will specifically focus on E. M. Hull’s phenomenon novel, The Sheik, detailing the reaction to it, some possible historical and cultural reasons why it illicit such a strong wave of interest and highlighting how this book became the mother of modern sheikh romance.